Tom Williams, writer of historical fiction, has just republished his book Cawnpore, about the Indian Mutiny. It is the second book in his trilogy entitled The John Williamson Papers, and is available from Amazon HERE.

I've read the whole trilogy and can most definitely recommend, especially if you have particular interest in the Victorian era. The first book in the series, The White Rajah, will be of particular interest to anyone who has enjoyed the new Jonathan Rhys Myers film Edge of the World - it is Tom's fictional version of this true story, and does, I believe, pay more attention to historical accuracy!

I hope you will enjoy this guest post from him... take it away, Tom :)

My book Cawnpore was first published in 2011, long before the recent resurgence of interest in Empire. It’s set in 1857 and we are immediately mired in controversy.

If there is controversy about the name of the place the book is set and what to call the events at the heart of the story, that’s nothing to the differences in the way that the people in the story are viewed. (Except for my fictional narrator, almost everybody in the book is a real person.)

The story of Cawnpore, whoever tells it, is a tragedy. British forces, surrendering after a long siege, were massacred. The Indian commanders attempted to save many of the women and children who had been trapped in the siege. Later, though, all the women and children were massacred in their turn.

|

| Artist: Jason Askew |

It was, by any standards, utterly appalling. It was used by the British to justify reprisals all across India, with the mass murder of men, most of whom were nowhere near Cawnpore and many of whom were not involved in any rebellion.

The Memorial Well on

the site of the massacre, photographed in 1860

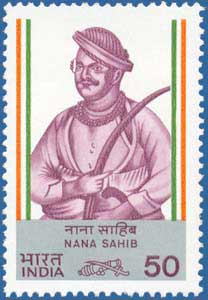

Both Indians and Europeans have much to be ashamed of. Yet until late in the 20th century, Cawnpore was taught in British history books as a story of native savagery. There was little discussion of why British troops were in India in the first place and nothing about the horrific reprisals against civilians. Now the pendulum has swung. The memorial on the site of the massacre has been removed and the park where it was has been renamed after the man responsible for the killings, Nana Sahib. He has been hailed as a hero of the liberation struggle. His image has even appeared on postage stamps.

The trouble with discussions of the rights and (multiple) wrongs of the Empire Project is that the issues are seldom as ethically clear-cut as modern commentators would like and the details of particular events have often been lost or lack context. In many ways, works of fiction can raise these issues more easily than history books. In my case, Cawnpore describes the events of 1857 as seen by a European who was there but who was horrified by the actions of both sides. The reader sees things as my fictional narrator saw them and then has to draw their own conclusions as to where their sympathies lie.'

🐘⚔🐘

Would you like to know more?

Tom's blog, on which you can read more about 19th century history, about his other historical series, thoughts on writing, and much other assorted random stuff!

Follow Tom on Twitter